The Shiite factor

The Shiite factor

Long vilified as extremists, these Muslims may hold the key to a new Middle East

By Jay Tolson

Blunt words are not the usual fare of Washington think-tank gatherings. But American Enterprise Institute fellow Reuel Marc Gerecht served up a few at a recent roundtable discussion. "If Iraq fails," warned the former CIA analyst, "we're toast."

Even if many Americans might question the extremity of that forecast, most can at least understand some of the reasons behind it. Leaving Iraq in anarchy after the election would mean that the loss of American and Iraqi lives was largely pointless. A premature departure would also result in a further loss of U.S. prestige in the Middle East. What most Americans may not appreciate, however, is the vital importance of Iraq to the future of the Islamic world--and particularly to those internal sectarian and ideological struggles to define Islam and its role in states and societies. At stake, above all, is whether radical Islamist extremism of the al Qaeda variety will prevail over more progressive, tolerant interpretations and uses of the faith.

Long history. Surprisingly, no players may be more important to the outcome of those struggles than the Shiite Muslims of the Middle East. Belonging to a sect that constitutes roughly 10 to 15 percent of the world's Muslims, Shiites trace their origins to a succession fight for the caliphate in the early decades after the death of Mohammed. (They insisted that only kinsmen of the Prophet could be rightful caliphs; those who prevailed and became the vast majority of the world's Muslims, the Sunni, believed that caliphs need only come from the community of believers.) While the majority of Shiites live in Iran, Central Asia, and South Asia, those living in Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and other parts of the Arab core of the Middle East (where Shiism originated) have often found themselves treated as second-class citizens--or worse--by their Sunni overlords, even in Bahrain and Iraq, where Shiites predominate.

Directly at issue in Iraq is not only the question of whether the nation's Shiite Muslim majority, some 60 percent of the population, will acquire political influence commensurate with its numbers for the first time in modern Iraqi history. (The political marginalization of Shiites began when the British mandate officials installed a Sunni Hashemite king in 1921, and Sunnis have dominated assorted Iraqi regimes ever since.) Just as important is whether the various Shiite movements, parties, and leaders--some more religious than others--will forgo triumphalism to support the creation of an inclusive democracy that is respectful of the rights of non-Shiites, Muslim or not. "Iraq can offer an alternative [to Islamist theocracies] if religion can be an influence on governance without being the political authority," says Nadeem Kazmi, head of international development at the London-based Al-Khoei Foundation, an Islamic charitable and development institute.

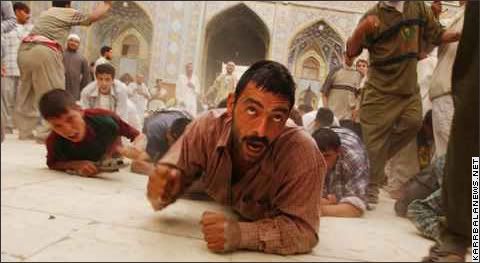

Because a favorable outcome in Iraq will depend largely on the Shiites, its achievement will be difficult unless Americans overcome an acquired uneasiness with the Shiite community. The reasons for that distrust are many. One is a partial misperception of Shiism as an extremist, emotionalist (particularly in their ritual acts of self-flagellation), and utopian minority of the world's Muslims, a view partly encouraged by western academic bias, which often leans toward the more western-oriented Sunni Ottomans and their heirs in modern Turkey. Another reason for U.S. wariness is rooted in a more practical political reflex inherited from European powers that once dominated large parts of the Muslim world: a predilection for working with Sunni Muslims while playing a game of divide-to-conquer with the Shiite and Sunni populations. Perhaps the greatest reason, though, is that Americans associate Shiism with the tumultuous Iranian Revolution of 1979, in which the Shiite cleric Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini installed a severe, repressive theocracy that derived much of its legitimacy from virulent anti-Americanism. To Americans, not surprisingly, the term "Shiite" became almost synonymous with "extremist radical."

Bridges to build. If Americans have tended to harbor little fondness for Shiites, it is a bias they can no longer afford, say Gerecht and other Middle East experts. Brandeis University historian Yitzhak Nakash, currently a fellow at Washington's Woodrow Wilson Center and author of The Shi'is of Iraq, put the challenge neatly in a recent presentation: "To contain the spread of Sunni radicalism, the United States will need to build bridges to those Shiites in the Arab world as well as to the reformers in Iran who have attempted to reconcile Islamic and western concepts of government."

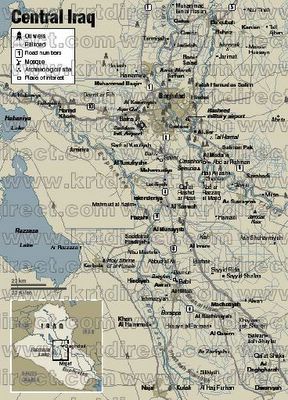

Efforts to build such bridges were slow in coming in Iraq, even as a largely Sunni-led extremist insurgency grew in strength and lethality. While part of the U.S. administration for a time placed considerable stock in the Iraqi National Congress, led by Shiite businessman Ahmed Chalabi, it initially neglected the religious leadership in the holy cities of Najaf and Karbala. That neglect came in part from failing to discriminate between the largely nonpolitical, "quietist" orientation of Iraq's religious establishment and the hyper-activist theocratic tendencies of Iran's ruling clerics. Unlike Khomeini's successors, Iraq's Grand Ayatollah Ali Sistani embraces a more traditional Shiite commitment to a separation of mosque and state, as long as the latter respects Islamic traditions and law ( sharia ). But even many U.S. Middle East experts did not fully appreciate Sistani's importance until after he defused tensions between U.S. forces and Moqtada al-Sadr by ordering the radical Shiite leader to vacate Najaf's Imam Ali Mosque.

A major cause of upheaval within the Islamic world is a crisis of religious authority, which developed, Al-Khoei's Kazmi explains, in tandem with a crisis of governance in modern predominantly Muslim states. To bolster their power, authoritarian rulers in Syria, Egypt, and elsewhere have variously suppressed restive religious leaders or cynically exploited more compliant ones. Not surprisingly, particularly within Sunni Islam, where lines of religious authority are relatively weak, self-made sheiks and mullahs have popped up all over the Middle East, proclaiming fatwas that justify even the most un-Islamic practices (including the killing of innocent civilians in the name of holy war).

Tolerance. Amid this crisis of authority and governance, says Yusuf al-Khoei, a director of the Al-Khoei Foundation, the Shiites have many things to offer, including an appreciation for tolerance. Grandson of a Najaf grand ayatollah who died under Saddam-imposed house arrest in 1992 and nephew of cleric Abdul Majid al-Khoei, who was killed in Najaf in April 2003 shortly after returning to Iraq from England to work for peace in the newly liberated country, the soft-spoken man would have every reason to be embittered by decades of Sunni mistreatment of Shiites. But a key goal of the foundation he works for is cooperation and reconciliation with the Sunnis. "We have always maintained good relations with the Sunnis," Khoei says, "because we know in order for things to work in Iraq and throughout the world, we have to cooperate."

Al-Khoei is not alone in seeing the Shiites as a counterweight to intolerant Salafi Wahhabism, that narrow, literalistic, and increasingly widespread approach to the faith that declares all other interpretation of the sacred texts and all other sects, whether Shiism or mystical Sufism, as sinful innovations. Says Sami Zubaida, a professor emeritus of politics and sociology at the University of London's Birkbeck College, "By contrast with that [Salafist Islamist perspective], the Shia world is more hopeful and encouraging. It is more culturally complex--tolerating philosophy, mysticism, and other forms of learning. There are legitimate grounds for saying that there is greater hope for flexibility coming out of the Shiite world, where there is more nuance, complexity, and less fundamental antagonisms toward the West."

Bridges to build. If Americans have tended to harbor little fondness for Shiites, it is a bias they can no longer afford, say Gerecht and other Middle East experts. Brandeis University historian Yitzhak Nakash, currently a fellow at Washington's Woodrow Wilson Center and author of The Shi'is of Iraq, put the challenge neatly in a recent presentation: "To contain the spread of Sunni radicalism, the United States will need to build bridges to those Shiites in the Arab world as well as to the reformers in Iran who have attempted to reconcile Islamic and western concepts of government."

Efforts to build such bridges were slow in coming in Iraq, even as a largely Sunni-led extremist insurgency grew in strength and lethality. While part of the U.S. administration for a time placed considerable stock in the Iraqi National Congress, led by Shiite businessman Ahmed Chalabi, it initially neglected the religious leadership in the holy cities of Najaf and Karbala. That neglect came in part from failing to discriminate between the largely nonpolitical, "quietist" orientation of Iraq's religious establishment and the hyper-activist theocratic tendencies of Iran's ruling clerics. Unlike Khomeini's successors, Iraq's Grand Ayatollah Ali Sistani embraces a more traditional Shiite commitment to a separation of mosque and state, as long as the latter respects Islamic traditions and law ( sharia ). But even many U.S. Middle East experts did not fully appreciate Sistani's importance until after he defused tensions between U.S. forces and Moqtada al-Sadr by ordering the radical Shiite leader to vacate Najaf's Imam Ali Mosque.

A major cause of upheaval within the Islamic world is a crisis of religious authority, which developed, Al-Khoei's Kazmi explains, in tandem with a crisis of governance in modern predominantly Muslim states. To bolster their power, authoritarian rulers in Syria, Egypt, and elsewhere have variously suppressed restive religious leaders or cynically exploited more compliant ones. Not surprisingly, particularly within Sunni Islam, where lines of religious authority are relatively weak, self-made sheiks and mullahs have popped up all over the Middle East, proclaiming fatwas that justify even the most un-Islamic practices (including the killing of innocent civilians in the name of holy war).

Tolerance. Amid this crisis of authority and governance, says Yusuf al-Khoei, a director of the Al-Khoei Foundation, the Shiites have many things to offer, including an appreciation for tolerance. Grandson of a Najaf grand ayatollah who died under Saddam-imposed house arrest in 1992 and nephew of cleric Abdul Majid al-Khoei, who was killed in Najaf in April 2003 shortly after returning to Iraq from England to work for peace in the newly liberated country, the soft-spoken man would have every reason to be embittered by decades of Sunni mistreatment of Shiites. But a key goal of the foundation he works for is cooperation and reconciliation with the Sunnis. "We have always maintained good relations with the Sunnis," Khoei says, "because we know in order for things to work in Iraq and throughout the world, we have to cooperate."

Al-Khoei is not alone in seeing the Shiites as a counterweight to intolerant Salafi Wahhabism, that narrow, literalistic, and increasingly widespread approach to the faith that declares all other interpretation of the sacred texts and all other sects, whether Shiism or mystical Sufism, as sinful innovations. Says Sami Zubaida, a professor emeritus of politics and sociology at the University of London's Birkbeck College, "By contrast with that [Salafist Islamist perspective], the Shia world is more hopeful and encouraging. It is more culturally complex--tolerating philosophy, mysticism, and other forms of learning. There are legitimate grounds for saying that there is greater hope for flexibility coming out of the Shiite world, where there is more nuance, complexity, and less fundamental antagonisms toward the West."

An important factor behind that flexibility is the fact that interpretation of the sacred texts remains open within Shiism, whereas within Sunni Islam the gates of interpretation ( ijtihad ) supposedly closed in the 10th century. Even Iran's Khomeini, for all his austerity, believed that the Koran had to be made relevant to the modern world. In addition to flexibility, Shiism suffers less from the general Islamic crisis of authority because it has unmistakable centers and figures of religious authority. Because there is widespread respect for Sistani--whose popular website makes his religious judgments available around the world--there is less chance that renegade mullahs such as Moqtada al-Sadr can ignore his rulings.

This is not to say that a Shiite-dominated political regime in Iraq will immediately satisfy all western notions of a modern, liberal democracy. And there will be debates--even within the broad Shiite coalition that Sistani has cobbled together--over how much Islamic law will shape the constitution and family and personal law. But there is strong evidence that Sistani is open to compromises. "He is particularly flexible," Nakash says, "and so are his most likely successors." Nakash goes on to elaborate that Sistani wants neither a theocracy nor a completely secular state: "We have to expect something that is neither the Iran of Khomeini nor the Turkey of Ataturk."

Tactics. Almost every supporter of a favorable outcome in Iraq agrees that America must be a careful midwife, exercising tact in diplomacy and greater shrewdness in its strategic thinking. Even being too cozy with Sistani might not be a good thing, particularly if he is perceived to be a U.S. lackey. And Iraq's chances of subduing the insurgency might be greatly helped, says Thomas Barnett, author of The Pentagon's New Map: War and Peace in the Twenty-First Century and a former professor at the U.S. Naval War College, if Washington tries to make Iran a more responsible player in the region. Tact means avoiding inflammatory labels such as "axis of evil" (which only rallies support for the shaky theocracy), and shrewdness means coming up with bargaining chips to draw Tehran away from building the Bomb. As he argues in a current Esquire article, Barnett believes that a more responsible Iran is more likely to change. "They will be influenced by what is happening in Iraq," he says. "Sistani may be their Lech Walesa."

Above all, urges Khoei, Washington should resist the colonialist habitof playing Shiites against Sunnis, Sunnis against Shiites, in Iraq and elsewhere. "Iraq is now the key," he says. "If the United States leaves a divided country, this will destroy America's image. People are wondering if America is dividing the Muslim world or uniting it. I hope it is using its influence to help unite it."

Long vilified as extremists, these Muslims may hold the key to a new Middle East

By Jay Tolson

Blunt words are not the usual fare of Washington think-tank gatherings. But American Enterprise Institute fellow Reuel Marc Gerecht served up a few at a recent roundtable discussion. "If Iraq fails," warned the former CIA analyst, "we're toast."

Even if many Americans might question the extremity of that forecast, most can at least understand some of the reasons behind it. Leaving Iraq in anarchy after the election would mean that the loss of American and Iraqi lives was largely pointless. A premature departure would also result in a further loss of U.S. prestige in the Middle East. What most Americans may not appreciate, however, is the vital importance of Iraq to the future of the Islamic world--and particularly to those internal sectarian and ideological struggles to define Islam and its role in states and societies. At stake, above all, is whether radical Islamist extremism of the al Qaeda variety will prevail over more progressive, tolerant interpretations and uses of the faith.

Long history. Surprisingly, no players may be more important to the outcome of those struggles than the Shiite Muslims of the Middle East. Belonging to a sect that constitutes roughly 10 to 15 percent of the world's Muslims, Shiites trace their origins to a succession fight for the caliphate in the early decades after the death of Mohammed. (They insisted that only kinsmen of the Prophet could be rightful caliphs; those who prevailed and became the vast majority of the world's Muslims, the Sunni, believed that caliphs need only come from the community of believers.) While the majority of Shiites live in Iran, Central Asia, and South Asia, those living in Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and other parts of the Arab core of the Middle East (where Shiism originated) have often found themselves treated as second-class citizens--or worse--by their Sunni overlords, even in Bahrain and Iraq, where Shiites predominate.

Directly at issue in Iraq is not only the question of whether the nation's Shiite Muslim majority, some 60 percent of the population, will acquire political influence commensurate with its numbers for the first time in modern Iraqi history. (The political marginalization of Shiites began when the British mandate officials installed a Sunni Hashemite king in 1921, and Sunnis have dominated assorted Iraqi regimes ever since.) Just as important is whether the various Shiite movements, parties, and leaders--some more religious than others--will forgo triumphalism to support the creation of an inclusive democracy that is respectful of the rights of non-Shiites, Muslim or not. "Iraq can offer an alternative [to Islamist theocracies] if religion can be an influence on governance without being the political authority," says Nadeem Kazmi, head of international development at the London-based Al-Khoei Foundation, an Islamic charitable and development institute.

Because a favorable outcome in Iraq will depend largely on the Shiites, its achievement will be difficult unless Americans overcome an acquired uneasiness with the Shiite community. The reasons for that distrust are many. One is a partial misperception of Shiism as an extremist, emotionalist (particularly in their ritual acts of self-flagellation), and utopian minority of the world's Muslims, a view partly encouraged by western academic bias, which often leans toward the more western-oriented Sunni Ottomans and their heirs in modern Turkey. Another reason for U.S. wariness is rooted in a more practical political reflex inherited from European powers that once dominated large parts of the Muslim world: a predilection for working with Sunni Muslims while playing a game of divide-to-conquer with the Shiite and Sunni populations. Perhaps the greatest reason, though, is that Americans associate Shiism with the tumultuous Iranian Revolution of 1979, in which the Shiite cleric Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini installed a severe, repressive theocracy that derived much of its legitimacy from virulent anti-Americanism. To Americans, not surprisingly, the term "Shiite" became almost synonymous with "extremist radical."

Bridges to build. If Americans have tended to harbor little fondness for Shiites, it is a bias they can no longer afford, say Gerecht and other Middle East experts. Brandeis University historian Yitzhak Nakash, currently a fellow at Washington's Woodrow Wilson Center and author of The Shi'is of Iraq, put the challenge neatly in a recent presentation: "To contain the spread of Sunni radicalism, the United States will need to build bridges to those Shiites in the Arab world as well as to the reformers in Iran who have attempted to reconcile Islamic and western concepts of government."

Efforts to build such bridges were slow in coming in Iraq, even as a largely Sunni-led extremist insurgency grew in strength and lethality. While part of the U.S. administration for a time placed considerable stock in the Iraqi National Congress, led by Shiite businessman Ahmed Chalabi, it initially neglected the religious leadership in the holy cities of Najaf and Karbala. That neglect came in part from failing to discriminate between the largely nonpolitical, "quietist" orientation of Iraq's religious establishment and the hyper-activist theocratic tendencies of Iran's ruling clerics. Unlike Khomeini's successors, Iraq's Grand Ayatollah Ali Sistani embraces a more traditional Shiite commitment to a separation of mosque and state, as long as the latter respects Islamic traditions and law ( sharia ). But even many U.S. Middle East experts did not fully appreciate Sistani's importance until after he defused tensions between U.S. forces and Moqtada al-Sadr by ordering the radical Shiite leader to vacate Najaf's Imam Ali Mosque.

A major cause of upheaval within the Islamic world is a crisis of religious authority, which developed, Al-Khoei's Kazmi explains, in tandem with a crisis of governance in modern predominantly Muslim states. To bolster their power, authoritarian rulers in Syria, Egypt, and elsewhere have variously suppressed restive religious leaders or cynically exploited more compliant ones. Not surprisingly, particularly within Sunni Islam, where lines of religious authority are relatively weak, self-made sheiks and mullahs have popped up all over the Middle East, proclaiming fatwas that justify even the most un-Islamic practices (including the killing of innocent civilians in the name of holy war).

Tolerance. Amid this crisis of authority and governance, says Yusuf al-Khoei, a director of the Al-Khoei Foundation, the Shiites have many things to offer, including an appreciation for tolerance. Grandson of a Najaf grand ayatollah who died under Saddam-imposed house arrest in 1992 and nephew of cleric Abdul Majid al-Khoei, who was killed in Najaf in April 2003 shortly after returning to Iraq from England to work for peace in the newly liberated country, the soft-spoken man would have every reason to be embittered by decades of Sunni mistreatment of Shiites. But a key goal of the foundation he works for is cooperation and reconciliation with the Sunnis. "We have always maintained good relations with the Sunnis," Khoei says, "because we know in order for things to work in Iraq and throughout the world, we have to cooperate."

Al-Khoei is not alone in seeing the Shiites as a counterweight to intolerant Salafi Wahhabism, that narrow, literalistic, and increasingly widespread approach to the faith that declares all other interpretation of the sacred texts and all other sects, whether Shiism or mystical Sufism, as sinful innovations. Says Sami Zubaida, a professor emeritus of politics and sociology at the University of London's Birkbeck College, "By contrast with that [Salafist Islamist perspective], the Shia world is more hopeful and encouraging. It is more culturally complex--tolerating philosophy, mysticism, and other forms of learning. There are legitimate grounds for saying that there is greater hope for flexibility coming out of the Shiite world, where there is more nuance, complexity, and less fundamental antagonisms toward the West."

Bridges to build. If Americans have tended to harbor little fondness for Shiites, it is a bias they can no longer afford, say Gerecht and other Middle East experts. Brandeis University historian Yitzhak Nakash, currently a fellow at Washington's Woodrow Wilson Center and author of The Shi'is of Iraq, put the challenge neatly in a recent presentation: "To contain the spread of Sunni radicalism, the United States will need to build bridges to those Shiites in the Arab world as well as to the reformers in Iran who have attempted to reconcile Islamic and western concepts of government."

Efforts to build such bridges were slow in coming in Iraq, even as a largely Sunni-led extremist insurgency grew in strength and lethality. While part of the U.S. administration for a time placed considerable stock in the Iraqi National Congress, led by Shiite businessman Ahmed Chalabi, it initially neglected the religious leadership in the holy cities of Najaf and Karbala. That neglect came in part from failing to discriminate between the largely nonpolitical, "quietist" orientation of Iraq's religious establishment and the hyper-activist theocratic tendencies of Iran's ruling clerics. Unlike Khomeini's successors, Iraq's Grand Ayatollah Ali Sistani embraces a more traditional Shiite commitment to a separation of mosque and state, as long as the latter respects Islamic traditions and law ( sharia ). But even many U.S. Middle East experts did not fully appreciate Sistani's importance until after he defused tensions between U.S. forces and Moqtada al-Sadr by ordering the radical Shiite leader to vacate Najaf's Imam Ali Mosque.

A major cause of upheaval within the Islamic world is a crisis of religious authority, which developed, Al-Khoei's Kazmi explains, in tandem with a crisis of governance in modern predominantly Muslim states. To bolster their power, authoritarian rulers in Syria, Egypt, and elsewhere have variously suppressed restive religious leaders or cynically exploited more compliant ones. Not surprisingly, particularly within Sunni Islam, where lines of religious authority are relatively weak, self-made sheiks and mullahs have popped up all over the Middle East, proclaiming fatwas that justify even the most un-Islamic practices (including the killing of innocent civilians in the name of holy war).

Tolerance. Amid this crisis of authority and governance, says Yusuf al-Khoei, a director of the Al-Khoei Foundation, the Shiites have many things to offer, including an appreciation for tolerance. Grandson of a Najaf grand ayatollah who died under Saddam-imposed house arrest in 1992 and nephew of cleric Abdul Majid al-Khoei, who was killed in Najaf in April 2003 shortly after returning to Iraq from England to work for peace in the newly liberated country, the soft-spoken man would have every reason to be embittered by decades of Sunni mistreatment of Shiites. But a key goal of the foundation he works for is cooperation and reconciliation with the Sunnis. "We have always maintained good relations with the Sunnis," Khoei says, "because we know in order for things to work in Iraq and throughout the world, we have to cooperate."

Al-Khoei is not alone in seeing the Shiites as a counterweight to intolerant Salafi Wahhabism, that narrow, literalistic, and increasingly widespread approach to the faith that declares all other interpretation of the sacred texts and all other sects, whether Shiism or mystical Sufism, as sinful innovations. Says Sami Zubaida, a professor emeritus of politics and sociology at the University of London's Birkbeck College, "By contrast with that [Salafist Islamist perspective], the Shia world is more hopeful and encouraging. It is more culturally complex--tolerating philosophy, mysticism, and other forms of learning. There are legitimate grounds for saying that there is greater hope for flexibility coming out of the Shiite world, where there is more nuance, complexity, and less fundamental antagonisms toward the West."

An important factor behind that flexibility is the fact that interpretation of the sacred texts remains open within Shiism, whereas within Sunni Islam the gates of interpretation ( ijtihad ) supposedly closed in the 10th century. Even Iran's Khomeini, for all his austerity, believed that the Koran had to be made relevant to the modern world. In addition to flexibility, Shiism suffers less from the general Islamic crisis of authority because it has unmistakable centers and figures of religious authority. Because there is widespread respect for Sistani--whose popular website makes his religious judgments available around the world--there is less chance that renegade mullahs such as Moqtada al-Sadr can ignore his rulings.

This is not to say that a Shiite-dominated political regime in Iraq will immediately satisfy all western notions of a modern, liberal democracy. And there will be debates--even within the broad Shiite coalition that Sistani has cobbled together--over how much Islamic law will shape the constitution and family and personal law. But there is strong evidence that Sistani is open to compromises. "He is particularly flexible," Nakash says, "and so are his most likely successors." Nakash goes on to elaborate that Sistani wants neither a theocracy nor a completely secular state: "We have to expect something that is neither the Iran of Khomeini nor the Turkey of Ataturk."

Tactics. Almost every supporter of a favorable outcome in Iraq agrees that America must be a careful midwife, exercising tact in diplomacy and greater shrewdness in its strategic thinking. Even being too cozy with Sistani might not be a good thing, particularly if he is perceived to be a U.S. lackey. And Iraq's chances of subduing the insurgency might be greatly helped, says Thomas Barnett, author of The Pentagon's New Map: War and Peace in the Twenty-First Century and a former professor at the U.S. Naval War College, if Washington tries to make Iran a more responsible player in the region. Tact means avoiding inflammatory labels such as "axis of evil" (which only rallies support for the shaky theocracy), and shrewdness means coming up with bargaining chips to draw Tehran away from building the Bomb. As he argues in a current Esquire article, Barnett believes that a more responsible Iran is more likely to change. "They will be influenced by what is happening in Iraq," he says. "Sistani may be their Lech Walesa."

Above all, urges Khoei, Washington should resist the colonialist habitof playing Shiites against Sunnis, Sunnis against Shiites, in Iraq and elsewhere. "Iraq is now the key," he says. "If the United States leaves a divided country, this will destroy America's image. People are wondering if America is dividing the Muslim world or uniting it. I hope it is using its influence to help unite it."